Ni Hao! Or should I say, Hello!

It’s always a thrill to dive into the profound and enchanting ocean that is the Chinese language. Today, we’re going to embark on an exciting journey into the colorful world of Chinese idioms, or as we say in Mandarin, “Chengyu.”

These four-character phrases pack an extraordinary punch, often telling a story or encapsulating a profound meaning. So, fasten your seat belts because we’re about to delve into “20 Popular Chinese Idioms”!

This voyage will not only enhance your Mandarin proficiency but will also enrich your cultural understanding, and let’s be honest, isn’t it fun to dazzle your friends with your newfound linguistic gems? These idioms are like secret keys, unlocking the intricate beauty and wisdom embedded within the Chinese language.

From intriguing historical tales to philosophical musings, each idiom carries a story, a moral, a shared cultural experience. This isn’t just about language, my friends; it’s about peeking into the soul of one of the world’s oldest civilizations.

So, are you ready? Let’s embark on this Chinese idiom adventure together! Buckle up, and let’s roll!

What Exactly Are Chinese Idioms?

The term we often use in English, “Chinese idioms,” is known as 成语 (chéngyǔ) in Chinese. If we break it down, it translates to “formed words” or “already made words,” hinting at their established place in the language.

Crafted over thousands of years, these idioms draw upon a rich tapestry of ancient myths, philosophical musings, poetry, fairy tales, and folk tales. They stand as a testament to the enduring legacy of the Chinese language, and most importantly, to its continuous evolution.

Usually consisting of four characters, these idioms often carry allusions to the grandeur of ancient Chinese literature and historical events, thereby adding an extra dimension to their meanings.

Why Are Chinese Idioms Called 成語 (chéngyǔ)?

The moniker given to Chinese idioms, 成语 (chéngyǔ), is an eloquent indication of their nature. In Chinese, “成” translates as “already made” or “formed,” while “语” signifies “words.” Thus, combined, they denote phrases that have been formed and accepted into the language due to their widespread use. They are, in essence, well-crafted words that have withstood the test of time and have become an integral part of the Chinese language.

So, How Many Chinese Idioms Are There?

As to the exact number of Chinese idioms, there’s no hard and fast rule. Different sources peg the figure somewhere between 5,000 to 20,000! Although the majority of these idioms have their roots in ancient times, they remain in active use in contemporary Chinese, enriching conversations and writings alike.

What’s fascinating is that even in today’s digital age, new idioms are being coined within online Chinese communities and chat rooms, underlining the dynamic nature of the language.

When and How Are Chinese Idioms Used?

Whether you’re emphatically making a point during a heated debate, sincerely encouraging someone to persevere, or flaunting your command over the classics, Chinese idioms have a place in almost every situation. These idioms can bring out the subtleties in a conversation that might otherwise get overlooked. However, beware of misusing them, as that can lead to unintended meanings or confusion.

The intriguing thing about most four-character Chinese idioms is that they often refer to a legendary tale or a historical event. In doing so, they concisely highlight the key aspects of the story or incident, serving as an effective mnemonic device for learners. Students in China, right from elementary school to high school, commit thousands of such idioms to memory as part of their language education.

The Importance of Context with Chinese Idioms

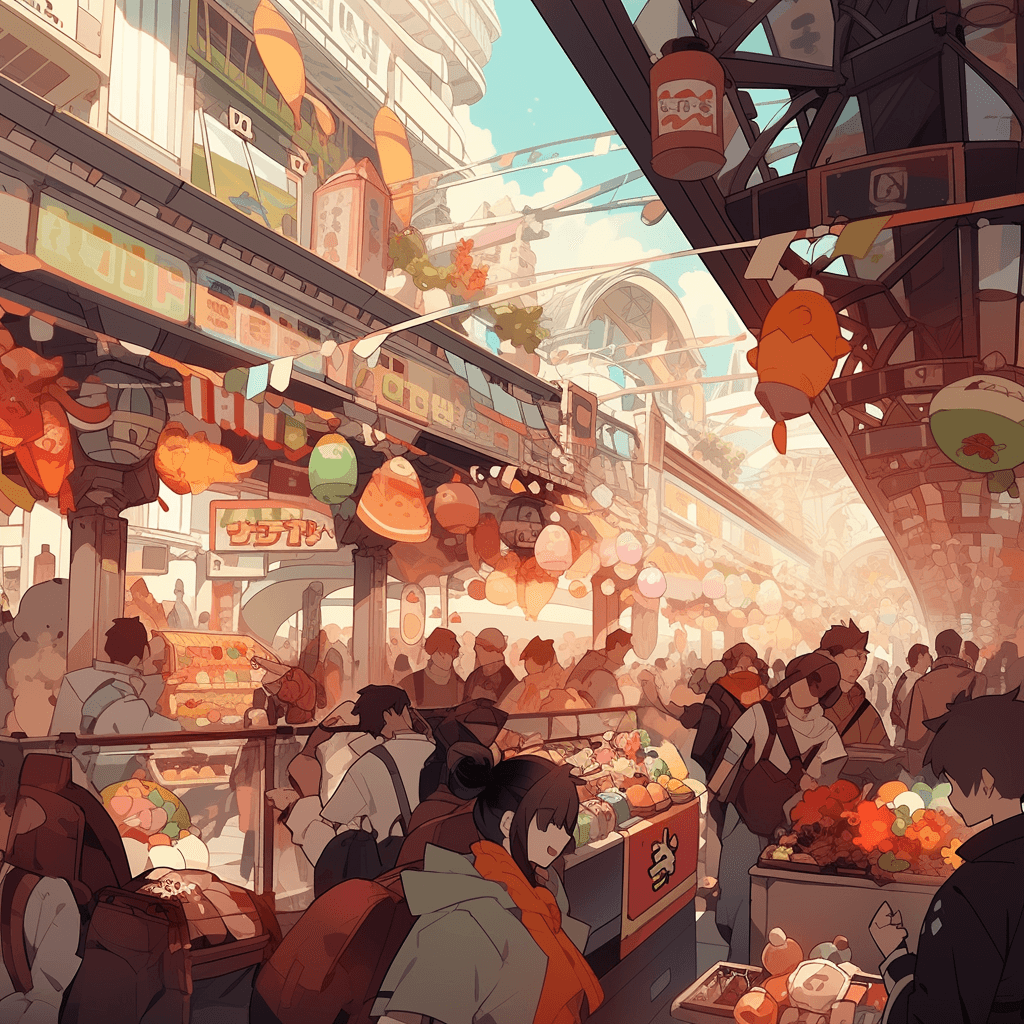

Consider the idiom 人山人海 (rénshān-rénhǎi), which literally translates to “people mountain, people sea.” Without understanding the context, you might be stumped about its meaning. But once you learn that it is used to describe a massive crowd or a multitude of people, the idiom suddenly makes sense. This understanding comes in handy when discussing social issues, crowded places, or expressing the idea that “China has a vast population.”

Origins of Chinese Idioms

Unpacking the origins of Chinese idioms can sometimes be a challenging task for Mandarin learners. Since these idioms are typically derived from classical Chinese texts or historical records, they often use unusual characters or employ familiar characters in unusual ways that seem to defy the rules of modern Chinese grammar. Therefore, understanding some idioms requires additional context beyond just knowing the meanings of the individual characters.

Chinese Idioms and Their Historical Significance

Two prime examples of how knowledge of Chinese history can illuminate the meanings of chéngyǔ are the idioms 破釜沉舟 (pòfǔ-chénzhōu) meaning “break the pots and sink the boats,” and 以一当十 (yǐyī-dāngshí) literally translating to “one to ten.” Without a grasp of their historical roots, these idioms can seem nearly indecipherable. However, with a bit of historical insight, their meanings become apparent.

Now that we know all about Chinese idioms, let’s learn 20 of the most famous idioms used!

20 Common Chinese Idioms 成语 (chéngyǔ)

| Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Literal Translation | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 馬馬虎虎 | 马马虎虎 | mǎmǎhǔhǔ | horse horse tiger tiger | Something that’s just passable or mediocre |

| 懸崖勒馬 | 悬崖勒马 | xuányálèmǎ | cliff reign in horse | Conveys the idea of stopping oneself in the face of impending danger |

| 騎虎難下 | 骑虎难下 | qíhǔnánxià | riding tiger hard dismount | A situation where someone is stuck in a difficult or dangerous position and finds it hard to extricate themselves |

| 守口如瓶 | 守口如瓶 | shǒukǒurúpíng | keep mouth like bottle | Keeping one’s mouth sealed like a bottle |

| 狡兔三窟 | 狡兔三窟 | jiǎotùsānkū | clever rabbit three burrows | It’s smart to have more than one plan or solution to a problem |

| 人山人海 | 人山人海 | rénshānrénhǎi | people mountain people sea | This is used to describe an extremely crowded place |

| 畫蛇添足 | 画蛇添足 | huàshétiānzú | draw snake add more | Overdoing something can ruin the whole effort |

| 狗急跳牆 | 狗急跳墙 | gǒujítiàoqiáng | dog urgently jumps wall | When someone is pushed to their limits, they can do desperate things |

| 守株待兔 | 守株待兔 | shǒuzhūdàitù | tree trunk wait rabbit | Waiting idly for success or opportunity without putting in effort |

| 亡羊補牢 | 亡羊补牢 | wángyángbǔláo | forget sheep mend the fold | Take action to fix a problem after a loss or mistake has already occurred |

| 半途而廢 | 半途而废 | bàntúérfèi | half way and abandoned | This idiom warns against giving up when one is halfway through a task or journey |

| 心有餘悸 | 心有余悸 | xīnyǒuyújì | heart has lingering fear | This idiom describes the feeling of unease that lingers after a frightful event |

| 拋磚引玉 | 抛砖引玉 | pāozhuānyǐnyù | throw brick attract jade | Offering something simple or unrefined in the hopes of inspiring or eliciting a more valuable response |

| 老馬識途 | 老马识途 | lǎomǎshítú | old horse knows the way | An experienced person is reliable and knowledgeable in guiding others or handling familiar tasks |

| 入木三分 | 入木三分 | rùmùsānfēn | enter wood three points | To express oneself clearly and deeply |

| 虎頭蛇尾 | 虎头蛇尾 | hǔtóushéwěi | tiger head snake tail | To start something enthusiastically but finish it poorly |

| 一鳴驚人 | 一鸣惊人 | yīmíngjīngrén | one cry surprises person | To suddenly rise to fame; to stun the world with a single brilliant feat |

| 杞人憂天 | 杞人忧天 | qǐrényōutiān | Qi persons worries about sky | A person who worries excessively about unlikely or imagined problems |

| 想入非非 | 想入非非 | xiǎngrùfēifēi | thinking enters not not | The act of letting your mind wander, of daydreaming, or indulging in wild fantasies |

| 青梅竹馬 | 青梅竹马 | qīngméizhúmǎ | green plum bamboo horse | Childhood friends who grow up playing together and share a deep, innocent bond |